‘Tis the season for history’s most famous communist

Now that Thanksgiving is over, it’s officially time to celebrate the Christmas season. That celebration invariably includes every streaming service in existence offering one version or another of Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. A quick IMDB search reveals at least 40 versions, including those staring the Muppets and the Flintstones. (In our house, we prefer the 1984 George. C. Scott version). I’ve read the book and seen the movies umpteen times, but it was only yesterday that I suddenly realized that Ebenezer Scrooge is a communist—although, thankfully, one who feels remorse and then repents and seeks redemption.

In case there is anyone unfamiliar with this 1843 novella, here goes:

Ebenezer Scrooge is a famously wealthy, unhappy, selfish, greedy money changer. The story begins on Christmas Eve day, when Scrooge calls Christmas a “humbug,” abuses his long-suffering clerk, Bob Cratchit, who has a large family including the disabled Tiny Tim, refuses requests for charity, and rejects his nephew’s attempt to bring him into the family fold.

That evening, when he goes home, he receives a visit from the ghost of his long-dead partner, Jacob Marley, who carries about him the clanking, heavy chains of his cold, money-grubbing life. He says that Scrooge will be visited by three spirits, giving him the chance to redeem himself.

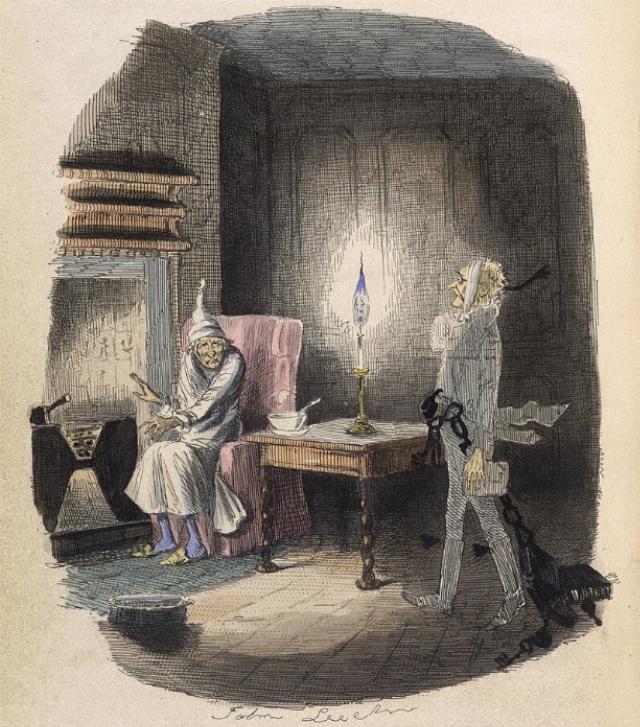

The image is John Leech’s original 1843 illustration of Scrooge and Marley. (Public domain.)

Over the next few hours, Scrooge is visited by the Ghost of Christmas Past, who takes Scrooge through his life, showing him how he changed from an open, loving young man into a mean miser, alienating all who loved him along the way. Next, he’s visited by the Ghost of Christmas Present, who lets Scrooge see into Bob Cratchit’s and his nephew’s happy homes, as well as showing Scrooge that ignorance and want plague the world.

Finally, the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come takes Scrooge into the future, where Scrooge sees the Cratchit family mourning Tiny Tim’s death and then, to his horror, sees the greed and happiness surrounding his own death.

When a broken Scrooge awakens, he’s thrilled to discover that it’s Christmas morning. He still has time to make amends, and, as Dickens writes, “it was always said of him that he knew how to keep Christmas well, if any man alive possessed the knowledge.”

If you hang around leftists, they’ll tell you that A Christmas Carol is an indictment of capitalism, even as they dismiss bourgeoisie notions about reform:

His legacy has been claimed by many. Bourgeois commentators stress his reforming zeal, claiming that he influenced a benevolent process of reform from above that, they say, characterised Victorian Britain. Even Prince Charles recently hailed Dickens’s "use of his creative genius… to campaign passionately for social justice". (Daily Telegraph, 7 February 2012)

What they neglect to mention, of course, was his anger, even despair, at the callous indifference of ‘the great and the good’ to the plight of the poor, and official inaction against the abuses he exposed. Even the sale of pauper boys as chimney sweeps was not finally banned until 1875, five years after Dickens’s death, and nearly 40 years after his novel, Oliver Twist, denounced the practice.

On the other hand, radicals, reformers, and socialists, from the Chartists to Tony Benn, have used his grim depictions of the workhouse, child abuse, prisons, bureaucratic incompetence of the state, and the cold inhumanity of factory owners, to inform their struggle for a better society. Karl Marx said that the great Victorian novelists, Dickens, Thackeray, and the Brontes, "have issued to the world more political and social truths than have been uttered by all the professional politicians, publicists and moralists put together". (The English Middle Class, Marxist Internet Archive)

However, the bourgeoisie class is correct here. As the same article quoted above acknowledges, Dickens was no socialist. His ideas were purely middle-class and focused on personal betterment and the voluntary community being responsible for mending social ills.

I’m not the first to point this out, but I’d like to move the focus from the book in its entirety to Scrooge specifically. Ebenezer Scrooge, before his conversion, isn’t just a mean man. He is the quintessential Western communist. Every expression he makes aligns with modern leftist values:

Scrooge is obsessed with money. You’ll find no people more obsessed with money than Western leftists. Because so many believe that Marxism is an economic system—it is, more accurately, a cult that, in the 19th century, used money as its selling point and, in the 21st century, uses culture to sell the cult—it is Marxists who place a monetary value on all things. They are the ultimate materialists.

Scrooge hates Christmas. There’s very little distance between “Bah! Humbug” and the left’s insistence on removing Christmas from the public sphere, whether it’s ending creches on public lands, Christmas carols in schools, or the very expression “Merry Christmas.”

Scrooge’s hatred for Christmas means he hates Christianity. The left has been engaged in an ongoing attack on Judeo-Christian principles for over a century. Leftists understand that people can serve only one master and, for them, the battle is between the state and God. The latest front in this war is the battle against the sexual binary, which is integral to the Biblical story of creation. Scrooge, by disdaining Jesus’s birth, is showing that he, too, hates Christianity.

Scrooge believes that government charity displaces private charity. Studies and polls repeatedly show that conservatives give more to charity. It’s not hard to figure out why: leftists believe that it’s the government’s, not the individual’s, responsibility to care for the widows and orphans. Scrooge would agree:

“At this festive season of the year, Mr. Scrooge,” said the gentleman, taking up a pen, “it is more than usually desirable that we should make some slight provision for the poor and destitute, who suffer greatly at the present time. Many thousands are in want of common necessaries; hundreds of thousands are in want of common comforts, sir.”

“Are there no prisons?” asked Scrooge.

“Plenty of prisons,” said the gentleman, laying down the pen again.

“And the Union workhouses?” demanded Scrooge. “Are they still in operation?”

“They are. Still,” returned the gentleman, “I wish I could say they were not.”

“The Treadmill and the Poor Law are in full vigour, then?” said Scrooge.

“Both very busy, sir.”

“Oh! I was afraid, from what you said at first, that something had occurred to stop them in their useful course,” said Scrooge. “I am very glad to hear it.”

“Under the impression that they scarcely furnish Christian cheer of mind or body to the multitude,” returned the gentleman, “a few of us are endeavouring to raise a fund to buy the poor some meat and drink, and means of warmth. We choose this time, because it is a time, of all others, when Want is keenly felt, and Abundance rejoices. What shall I put you down for?”

“Nothing!” Scrooge replied.

“You wish to be anonymous?”

“I wish to be left alone,” said Scrooge. “Since you ask me what I wish, gentlemen, that is my answer. I don’t make merry myself at Christmas, and I can’t afford to make idle people merry. I help to support the establishments I have mentioned—they cost enough: and those who are badly off must go there.”

Today’s communists hate prisons and don’t believe people should work for welfare, but the underlying principle is unchanged: Each believes that, because of government institutions, the widows and orphans aren’t his responsibility.

Scrooge believes in the benefits of depopulation. Leftists have long believed that the earth is overpopulated and that humans must be culled. This, too, is anti-Christian because (a) it’s antithetical to the Biblical mandate to “be fruitful and multiple, and (b) it’s an extreme form of Gaia worship—that is, pre-Christian paganism. In 2006, for example, University of Texas ecologist Eric Pianka announced that 90% of all humans need to die to save the planet. Both the WEF and the UN are dedicated to depopulation.

When Scrooge insists to the men seeking donations that the workhouses are already in place, obviating the need for him to pay even more, one of the men explains, “Many can’t go there; and many would rather die.” Scrooge’s response would make leftists proud: “‘If they would rather die,’ said Scrooge, ‘they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.’”

Thankfully, by the end of the book, Scrooge has recognized that the government is not responsible for healing the world’s ills, nor would the world be better off if the population were culled. Instead, as Dickens makes clear—and Christmas reminds us—each of us is “our brother’s keeper,” and it is up to us, through our individual choices, to improve life for all.