Roger Scruton: A Devotion to Liberty and Beauty

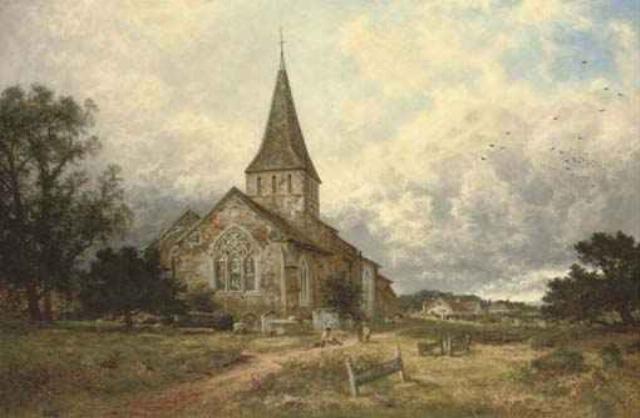

From Wikimedia Commons: The Village Church (Benjamin Williams Leader, 1894)

A philosopher and cultural warrior, Roger Scruton (1944–2020) dedicated his life to defending the principles of liberty, beauty, and tradition against the high tide of revolutionary ideology. In a modern world seduced by utilitarian and utopian doctrines, he stood firm, rooted in the conservative tradition of Edmund Burke and emphasizing the importance of continuity, moral order, and the transcendent value of culture.

Scruton’s lifelong commitment to liberty went beyond “armchair heroism”—it was a lived reality. Throughout his career, his ideological enemies (e.g., Marxist academics and journalists) exposed him to malicious harassment. Despite hostility from various quarters, he never wavered, though. An exemplary courage was evident in his support for political dissidents whom he personally visited behind the Iron Curtain. Abiding by the very values that he preached, he lent his voice to those struggling for freedom at the cost of career, privileges, and personal safety.

Highlighting the implications for our self-perception as humans and loyalty to a particular community (belonging), Scruton insisted that “beauty matters”—less as a “luxury” than as a “necessity for human flourishing”. He took issue with cultural nihilism, e.g., soulless modernist architecture, believing that the spaces that we inhabit and the art that we cherish shape our souls and societies. For him, beauty, apart from aesthetics, was about meaning, memory, and identity.

A cornerstone of Scruton’s philosophy was his reverence for “vernacular architecture”—the traditional, locally rooted building styles that arise naturally from a community’s history and environment. He saw these forms, not as antiquated relics but as living expressions of a people’s collective memory and cultural continuity. To him, the “vernacular home” was a sanctuary, embodying a tangible connection to the past, the land, and the shared narratives that define a community.

Scruton believed that the neglect of architectural traditions led to widespread alienation. Modernist architecture, with its universalizing, abstract forms, severed people from their sense of place and belonging. This rupture, he warned, produced a state of “cultural homelessness” where people lived in spaces that felt impersonal and disconnected from who they really were. His “love of home” (oikophilia) referred to something other than random shelter; it concerned the emotional and spiritual refuge emerging from an inhabited space that resonates with history, culture, and natural beauty.

For Scruton, love of home was intertwined with love of country and community. It was the foundation of rootedness and stability, a counterbalance to the restless-faithless cosmopolitanism and uprootedness of modern life. This love carried moral weight—it fostered responsibility, stewardship, and a commitment to preserving the environments, traditions, and relationships that nurture human life.

Scruton’s personal courage was matched by a gentle humor and warmth, making him a beloved figure among students and colleagues. His philosophy combined rigorous intellectual discipline with a deep empathy for the human condition. He understood that liberty is fragile and must be protected, depending partly on laws and institutions, partly on a shared cultural heritage nurturing the spirit.

Scruton’s ideas influenced public debates about architecture profoundly. An outspoken critic of the “totalitarian mindset” permeating modernist architecture (and “social engineering” in general), he argued that cold, functionalist designs ignored human needs for comfort, tradition, and aesthetic harmony. He challenged architects and planners to rethink the relationship between design, community, and culture—urging a return to styles and methods that respect historical continuity and local character.

This stance put Scruton at the center of heated discussions about urban planning and housing policy. He advocated for new developments rooted in place, using traditional materials and designs that fostered a “sense of belonging rather than alienation”. His work inspired movements aiming to revive classical and vernacular architecture as antidotes to the dystopian monotony and detachment of modernism.

Politically, Scruton’s architectural philosophy intertwined with his conservative outlook on society. He saw the denigration of traditional architecture as part of a broader cultural erosion that threatened social cohesion and political stability. For him, architecture was a visible symbol—a mirror—of the values that a society holds dear: order, beauty, and continuity. When those were sacrificed, so too was the foundation for a flourishing, free society.

Scruton’s thoughts contributed to debates about nationalism, localism, and identity, especially in an era marked by “globalization” and rapid social change. Neither parochial nor exclusionary, he insisted that love of home and place was a “necessary”, though not “sufficient”, condition for genuine community and political liberty. He warned against ideological schemes claiming to “liberate” people from their cultural and historical roots in the name of progress or utopia.

Besides confronting “progressives”, Scruton helped reframe cultural discussions within conservatism itself. He bridged the gap between intellectual conservatism and everyday life by showing how abstract ideas about tradition and beauty manifest in the built environment and emotional attachments of ordinary people. His voice was crucial in reminding political conservatives that culture and aesthetics are not trivial but foundational to a healthy society.

Building on the conservative tradition of Edmund Burke, Scruton reminded us that true progress is unattainable through a totalitarian break with the past. Instead, it must be fostered by a careful preservation and cultivation of the wisdom embedded in tradition. Scruton’s life’s work was a testament to the enduring power of beauty, the necessity of liberty, and our heavy responsibility to defend both against nihilist forces eager to denigrate—and destroy—them.

Scruton’s strong views placed him in the eye of controversy, especially when his conservative principles confronted prevailing trends in architecture, politics, and culture.

One notable controversy involved Scruton’s appointment in 2018 as the unpaid chairman of the UK government’s “Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission”, a body established to promote design standards in housing and urban development. Scruton’s task was to champion beauty and tradition in a political landscape dominated by cost-cutting, high-density modernist housing schemes. However, shortly after his appointment, manipulated excerpts from an interview with joint deputy editor George Eaton, New Statesman, painted him as “politically incorrect”, implying racist attitudes towards Jews, Muslims, and Chinese.

Scruton’s consequent dismissal sparked a fierce debate about free speech, cultural values, and the role of beauty in public policy. Supporters argued that his emphasis on traditional aesthetics was sorely needed in an era of bland, impersonal urban development and that his dismissal was a political foul-up driven by ideological intolerance. Critics, meanwhile, accused him of reactionary views out of step with modern, diverse societies.

Assignments apart, Scruton repeatedly clashed with proponents of modernist architecture and progressive urban planners who saw his focus on tradition as backward-looking and exclusionary. In debates about public housing, he insisted that providing cheap, functional buildings was never enough; designs must foster community and respect cultural identity. This stance was seen by some as “elitist” or “nostalgic”. Yet, it resonated with those feeling alienated by the impersonal scale and style of modernist experiments.

In academic circles, Scruton’s critiques of Marxism and postmodernism further fueled tensions. His defense of Western heritage and skepticism towards radical social change made him a lightning rod in ideological confrontations. Most of his critics, however, acknowledged the weight of his scholarship and his devotion to the values of liberty and cultural preservation.

Scruton’s consistent advocacy for beauty and tradition also influenced wider political-cultural discussions on nationalism and identity. His insistence that love of home and country was compatible with liberal democracy challenged both multiculturalist activists and cosmopolitan conservatives, encouraging a reassessment of how societies balance “diversity” with “social cohesion”.

Furthermore, Scruton’s outspoken defense of beauty, tradition, and conservative values inevitably placed him at the center of ideological controversies—some highly publicized and polarizing. His ideas challenged powerful currents in architecture, politics, and culture, sparking debates that extended far beyond academia (interfering with public policy and “media discourse”).

At the heart of Scruton’s life and work was a passionate devotion to liberty and civilization—principles that he considered absolutely indispensable and foundational to the flourishing of human life. For him, somebody speaking from personal experience, liberty was anything but a political abstraction; it was a living, fragile reality that depended on the cultural, moral, and spiritual fabric of society. Civilization, in turn, was the cultivated environment—both material and immaterial—that nurtured this freedom.